What Are We Doing?

Motivation

Sometimes I wonder what motivates me to play and teach music. Sure, I’m dedicated to my art for the sheer love of it, as I know many others are. Music is something that is fun and inspiring, so it seems obvious to me why I would want to devote a significant amount of time to it. It also requires quite a bit of hard work, patience, and discipline to be even a little good at it. Music is not easy, to say the least. I personally love this part of it, because I love a good challenge. That just happens to be how I’m wired. Similarly, I possess the same mindset with other things I enjoy, like drawing, skiing, and mountain biking. I find the better I am at something, the more I enjoy it, and the deeper I immerse myself into a challenging activity, the more I learn about myself. I would also assert that being good at something can boost one’s self-esteem, thus motivating that person to continue doing it. In my case, if I enjoy doing something enough, I want to put that extra effort into it so I can get the most out of. To say it more simply, the hard work is not a chore. It’s a labor of love. I figure if I’m not willing to make the effort at whatever it is I’m doing, then it is most likely something I didn’t really want to do to begin with - and so I don’t. Golf comes to mind.

For many, the discipline factor is a deal-breaker. I’ve encountered more than a few people who quit when the challenges start to mount. Or worse, they simply settle for mediocrity (which does not compute with me). Then, of course, there’s the expense - if you want an instrument that plays well and sounds half-decent, you need to spend some money. Along with that, there are lessons (which will also set you back some bucks). With lessons, practice should be understood (because why would you spend your hard-earned cash on a nice instrument and lessons - and not practice?), which brings us back to that dirty little word, “discipline.” The bottom line is, you have to put in the time if you want to be good at music (or anything for that matter). There’s no easy road… no shortcuts. I suppose someone could liberally define the word “good” any number of ways, choosing the one that best suits them, but then we start teetering on the fence that lies between excellence and mediocrity - a fence I tend to avoid at all costs. Besides, I think most of us can agree on what is good and what is not good.

Music Education

Last year my daughter decided to join the high school band. I, of course, supported that decision, since some of my fondest memories of high school were because of band, and I was happy that she now had an opportunity to make the same types of memories as well as some new friends. As her father, and now apparently a “band parent,” I wanted to contribute something worthwhile to the program, so I offered to help out with the drum line (free of charge), an offer the band director was all too eager to accept, since they didn’t have a full-time instructor. I thought since I have a good deal of experience both playing in band and some experience teaching drum line, I had something of value to offer the kids and the director. And it would be much more fun than organizing a fundraiser… or so I thought.

All seemed well at first. The kids filed in on the first day of percussion camp, socialized, and got caught up after a couple months of not seeing each other (which brought back memories for me… sniff, sniff). I met the other instructors and a few of the kids, and away we went. I left most of the instruction to the head drum instructor on the first day or two, to get a feel for how he taught and what the kids were used to (I’m not one to shake things up too much). Like all “first days,” it was shaky. There were more than a couple students relatively new to percussion, having switched over from another instrument for the marching season (not uncommon). However, as the day went on, there seemed to emerge a sense of cohesiveness. I thought “okay, I can work with this. Should be fun!” I had lofty plans. Help them get tight, reinforce the techniques and concepts conveyed by the head instructor (he would no longer be there after band camp), build some rapport with the kids, inspire them to do their best, teach them about teamwork (and, of course, music), and hopefully instill in them a sense of pride when they realize a common goal. I was very excited - but alas… it was not to be (sigh).

The vibe was uncomfortable from the start of the first sectional rehearsal. I was immediately taken aback by long faces and even some dirty looks coming from a couple of the kids (one of them, the section leader). The impression I was getting was that my presence there was not wanted. At first I thought it was just my imagination getting the best of me, since I had never experienced anything like that. But they never seemed to warm up to me. I didn’t quite know how to respond to the ice-cold vibe I was getting. Okay fine - far be it from me to cramp their style (remember, I was not being paid for this), so I showed them (and myself) mercy and bowed out. Besides, I was not interested in getting into some power struggle with teenagers that would last all season long (I’m way too old for that). As it turns out, my intuition was dead on. My daughter later informed me that the section leader just wanted to keep it “light and fun,” and that they really didn’t want me there, that they’d be just fine on their own. Fair enough.

Fun is all well and good (and I certainly was on the same page there. Unfortunately, they never gave me a chance to express that), but what about the learning part and working toward a goal? This is music education, after all. If fun is the only goal, they don’t need to be involved in a high school music activity for that. So, what were they doing there? It seems that, for them, the social aspect of band took precedence over the learning part. The music was just a formality. That being the case, I thought, “What am I doing here?” Obviously our objectives are not the same. As the old saying goes, “you can lead a horse to water…” (you know the rest). Not a good match. Glad I figured it out quickly. No harm done. moving on.

The Music Scene

I often attend weekly jam sessions. These are usually held on off-nights in clubs or restaurants where musicians can get together to hear music, play, hang, and make connections that will hopefully lead to future gigs. That’s the way I see it, anyway. And they’re fun (that’s important). It also gives local patrons a place to go where there is something happening on a weeknight, generating business for the establishment on a night when business might otherwise be slow (not to mention a weeknight gig for the host band… always a welcomed opportunity). If successful, it’s a win for everybody.

One night I was out at one of the sessions I frequently attend, and I mentioned in passing to someone there how much I enjoyed the session, but that it would also be nice to eventually land a gig or two out of it. Their response was that it really shouldn’t be about that. “It’s all about the vibe, the hang, and the music, man.” While I could see their point (which admittedly made me feel more than a little shallow for a moment), I also had to consider all the time and effort I’ve invested in this over the years, working hard to actually be good at it - lessons, formal education, practice, money spent on said education, gear, etc. Why shouldn’t I be seeking out a paying gig? Then I got to thinking, if anyone else who goes to school for a given course of study, upon graduation the expectation is, understandably, to use that education to search for employment, or at least to feel qualified enough to be employed in their respective field. Why should it be any different for me? Now, for the weekend warrior or hobby player who holds down a day job and does music on the side for fun, that whole “peace, love, and music” thing is valid (albeit, slightly hippie). Nothing wrong with that. But, quite frankly, that doesn’t pay my bills (not that I don’t enjoy some good “peace, love, and music…” I suppose I have a hippie side too).

This brings us back around to the original question. What are we doing? What are the goals? Personally, my goal has always been to make a respectable living doing the one thing I do best, play and teach drums. It’s why I went to school for it. So yes, it is my goal to network with great musicians and land paying gigs, and I don’t apologize for it one bit. Of course, I also want the experience to be good, and fun, and “vibey,” and all that. I definitely have standards - but who doesn’t? I won’t play with people whom I don’t feel are adequate, or whom I don’t click well with, because… well, that’s not fun for me. In fact, it’s utterly painful, and I’m not the martyring type… ha! We all want to find a line of work we love. Just because we might happen to enjoy our work doesn’t mean it isn’t worth its wages. I wonder what a nurse would say if someone told them they shouldn’t be paid for their service. They should be doing it because they love people and want to help them - for the good of all humanity, right? Yeah… not practical at all. Nursing school, and the student loans that come with it - it’s no joke. And neither is music school (I too had student loans). After all the years I’ve spent working so hard at my craft, I truly believe that yes, my work is worth its wages. Just like a nurse, or a plumber, or a lawyer, or a whatever…

Transparency

So, why do I do this? It’s pretty simple, really. I want to make good music with like-minded musicians who I enjoy being around, I want to share that with an appreciative audience, I want private students who are there to learn, grow, and enjoy music for music’s sake. and I’d like to make a respectable living doing it. It also needs to be fun, because a happy state of mind really is as important as paying the bills. If the all the boxes are checked, then I feel I’ve achieved something good. For me, that is the definition of a healthy work environment.

I also want to play at a level that I feel is above average. Maybe that’s partly my selfish ego talking, but I think it’s more than that. It goes back to that hard-work/fun relationship idea I previously discussed. A very wise jazz band director I studied under once said “music is only fun when it’s easy.” More often than not, it’s difficult at first. That’s where the grind begins. But the reward is well worth the blood, sweat, and tears. There’s a unique satisfaction that comes from working hard at something, believing in yourself, and ultimately achieving what you set out to do - and boy, is it ever satisfying. Oh, that rush of endorphins! I wish everyone could experience that kind of elation.

What about you? If you haven’t given it much thought, maybe a little self-analysis would be worthwhile. You never know what you will discover about yourself. Whatever it is you do, what motivates you to do it? That question can apply both to your work and to your leisure activities. What drives you? Are you passionate? Do you have clear and intentional goals? Are those goals practical? What is your mindset? What are you doing?

max roach: confirmation

Max Roach is arguably one of the most important figures in the development of modern jazz drumming. If you intend to study the style, he is one guy you don’t want to overlook. His time-keeping and solo vocabulary served as the foundation for which every other jazz drummer since then has built upon, and is still relevant today. Max’s playing style is, in a word, timeless.

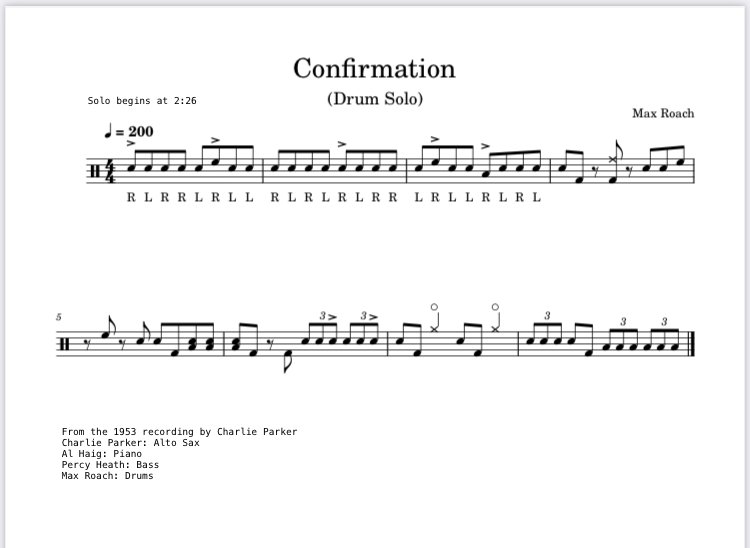

In this lesson we are going to take a look at a short solo from the 1953 Charlie Parker recording of “Confirmation.” The tune is a 32-bar AABA form, and the drum solo happens in the B section at 2:26, immediately following the bass solo. This solo is full of classic “Max-isms,” which you will most likely come across if you study other solo transcriptions of him… which I would encourage you to do.

I’ve included the original recording below, as well as my own transcription, and a short video of me demonstrating the solo beginning at a very slow tempo, and increasing to the tempo on the recording. I have included stickings for the first three measures so you don’t have to figure that out. When I was learning the solo, I first tried alternate sticking (which would work), but ultimately settled on paradiddles, because I thought it flowed better and actually sounded more like the way Max played it. Also, take note of how Max plays the rhythm in the first three bars as straight eighth-notes. He doesn’t swing the eighth-notes until the fourth bar.

As with anything, take your time, and work out the solo slowly until you can play it in time (always practice with a metronome), then gradually work it up to speed. Have fun!

Setting Up Your Drums for Success

How you set up your drums is personal at best. These days drum manufacturers are designing hardware that allows you to adjust your drums and cymbals at virtually any height and angle, and so providing infinite possibilities. While this may be beneficial, it could potentially make things more confusing for a beginner who is setting up their drums for the first time. So, where is a good place to start?

The best advice I have ever got was from Ed Soph, who said to think of the drum set as if it were one big snare drum. What this means is to position things in a way so they are close together and easily accessible so that you are hitting the drums in the center of the head. Everything should be an extension of the snare drum, which is central to the drum set. If you have to fully extend your arms to hit a drum or a cymbal, you may have positioned it too high and/or too far away. Also, be careful not to angle the drums at too steep of a slope. I have seen beginning students angle their toms to the point where the shells are almost parallel with the floor. This is probably not the best way to position any drum since when we play, our sticks basically move in an up and down (not forward) motion. Plus, you’ll run a much higher risk of denting heads like that. They should be angled some, but it depends on how high or how low you sit (another topic for another time). The same rule applies to cymbals. You want to be able to hit them both with the tip of the sticks and also on the edge of the cymbal with the shoulder of the stick. If both types of strokes are not possible with your current setup, maybe reevaluating the height and angle of your cymbals would be in order.

As I mentioned earlier, how you set up your drums is personal. Your physical size will more than likely factor into how you position things. I’m not very big guy (about 5’ 5”), so my set up might not feel comfortable to someone who is taller (and vice-versa). Your choice of grip will also influence your setup. Many players who play traditional grip tend ot angle the drums differently (especially the snare) than a matched grip player. It’s important to understand that the traditional grip was originally developed to accommodate the natural slope of the old rope-tensioned marching drums. Most traditional grip players tend to set their snare up a little higher, sloped down, and slightly to the right to follow the natural slope of the left-hand stick. Matched grip players will usually position their snare drum flatter or slightly angled toward them.

I hope you have found this information useful in some way. some self evaluation is never a bad thing. In most cases, it can help to affirm the things we are doing that are working, and hopefully help correct the things that are not working. The ultimate goal is to make good music, and we don’t want our setup to hold us back from that goal. Good luck!